Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies are transforming the way we interact with digital environments, but for some, these innovations present new challenges. Atieh Taheri, a postdoctoral fellow at Carnegie Mellon University’s Human-Computer Interaction Institute, offers insights from her personal experience with VR that illuminate the broader conversation on accessibility in tech development.

Despite Taheri’s enthusiasm for VR, her initial experience was less than seamless. Having never walked due to spinal muscular atrophy, the simulation of head bobbing while moving through a virtual world was disorienting. “To me, it felt like people with motor disabilities weren’t considered when designing VR systems,” she observed.

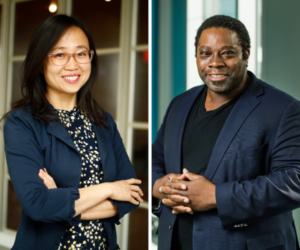

Taheri, along with her collaborators, is researching ways to tailor VR experiences for those unfamiliar with these sensations. Their work underscores the importance of integrating accessibility features in the burgeoning fields of AR and VR early in the design process. As David Lindlbauer, an assistant professor at HCII, notes, “Accessibility still feels like an afterthought for a lot of VR and, especially, AR experiences.”

Lindlbauer’s colleague, Patrick Carrington, shares similar concerns. With a background in web development, Carrington has seen firsthand the delays caused when accessibility is not prioritized from the start. His current research focuses on wearable technology and how it can be adapted to meet the needs of users with disabilities.

One area of Carrington’s research involves the creation of WheelPoser, a novel system for motion tracking that requires only four sensors, making it more practical for everyday use. “You need to either have a giant studio with a bunch of cameras and wear a special suit, or wear 17 or so sensors on your body that you’d have to strap on and calibrate,” Carrington explained. WheelPoser simplifies this with one sensor on each forearm, one on the forehead, and another on the wheelchair.

As the shift toward headsets and camera-based systems continues, Carrington’s Axle Lab explores how people with motor impairments might interact with these devices, studying how to create intuitive hand gestures and motion controls.

Taheri’s own journey into accessibility research was sparked by her loss of fine motor skills, which led her to explore hands-free gaming controllers through facial-expression recognition. Her work, like Carrington’s, aims to ensure that advancements in VR and AR are inclusive and adaptable for various impairments.

The potential applications of VR and AR are vast, ranging from training programs for firefighters to remote surgical assistance. As Lindlbauer highlights, these technologies can also enhance experiences for those with limited mobility or visual impairments. “Virtual worlds can account for things like visual deficiencies and do things such as change contrasts to make things easier to perceive,” he said.

Ultimately, Taheri emphasizes the societal barriers faced by people with disabilities and the role of technology in overcoming them. “Society is what truly disables people,” she stated. “Accessibility is not limited to only one group — it’s something that can benefit everyone at some point in their life.” Her work seeks to empower users by making digital environments more inclusive and accessible for all.

Read More Here